What a day! A mix of nostalgia, fear, adventure, and accomplishment.

A few weeks ago, I contacted Bob Gaines, owner of Vertical Adventures and co-author of a popular Tahquitz guidebook. Interesting tidbit: Bob was a climbing double for William Shatner in Star Trek: The Final Frontier (1989). I was interested in hiring a professional guide to lead me up a moderate multi-pitch at Tahquitz Rock, home to some of the finest alpine climbing this side of Yosemite. My new climbing buddy Ryan was interested in joining, and we spent the day at Suicide Rock with guide Tony Grice. Tony is a certified AMGA Rock Instructor and has logged lots of mileage on everything from the big walls in Yosemite to adventure routes in the Sierra. We did some mock leads on top rope and practiced anchor building and swinging leads up a 3rd class gully. It was a great learning experience, and Ryan and I spent the following weekend at Mission Gorge doing some more gully practice, and then I led the 2-pitch Skyline Pinnacle (5.7). Technically, we felt ready to tackle an easy multi-pitch a Tahquitz.

A bit of history. Growing up, I knew this granite wall as Lily Rock. My grandparents owned a cabin in nearby Pine Cove, and I must have been four or five the first time I laid my eyes on the towering pinnacle. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was the late 70’s, when Tobin Sorenson, John Long, and John Bachar were climbing hard and putting up new routes that would later become classics. It was the era of the Stone Masters, but I was busy catching bull frogs and dragonflies at Lake Fulmor.

On our guide day, I left San Diego early so that I could visit the old cabin. My grandpa passed away about 20 years ago, and my grandma sold the cabin a few years later. It’s hard to believe that so much time has passed. I drove up to the cabin just as the sun was starting to rise, and it looked exactly as I remember it. I was hit by a flood of memories. On cold winter days, my sister and I would clamber down the stairs and spend the mornings sitting on the bottom steps, directly in front of the heater. My grandma would make delicious pancakes and we would watch the scrub jays eat walnuts on the front porch railing. Idyllwild, Pine Cove, and Lily Rock all hold a special place in my heart, and my very first backpacking trip was with my uncle up Devil’s Slide Trail, out of Humber Park. These are some of my fondest memories from my childhood. The fact that Jasmine had just given birth to our first child a week earlier did nothing to quell the emotion I was feeling! I’m not a terribly spiritual person, but I found myself talking to my grandpa, and telling him about my life and my new son.

So, in a nutshell, leading a climb up Lily Rock would be a special experience.

Ryan and I departed for Tahquitz at 4 am with a very serious goal; we would climb The Trough (5.4), a 400 foot, 4-pitch route that served as the path of first ascent in 1936 (read: the easiest route up the face). Having led a few 5.6’s and 7’s with relative comfort, I didn’t expect The Trough to be quite so intimidating. As it turns out, the old-school ratings at Tahquitz live up to their reputation, and I found myself surprised at the difficulty. Although I’m getting better at dealing with exposure, I’ve never felt nearly as committed as this. When you’re 300 feet high on the rock and nearing the end of the rope, with only a few pieces of remaining pro hanging from your harness, there is something about life and the consequences of your actions that becomes crystal clear. At the risk of sounding overly dramatic, I felt alive.

We arrived at Humber Park just before dawn. Being so new to trad climbing, let alone multi-pitch, we knew it would be slow-going and we wanted to get an early start. I sure as hell didn’t want to be stuck up there in the dark. I planned to lead all the pitches and Ryan would follow and clean, and we racked up in the parking lot and started up the Ernie Maxwell Trail to the base of the rock. Twenty minutes later, we realized we had passed the signed turn-off for the climber’s path, and we turned around. We hoped this would be the first and only route-finding error of the day. Unfortunately, it would be the first of three.

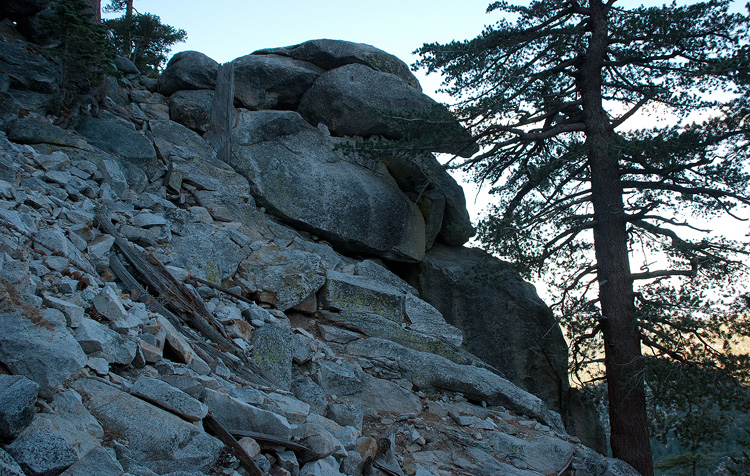

About 45 minutes later, we had huffed and puffed our way up to Lunch Rock, at the base of the west face of Tahquitz. It wasn’t long ago that I was in pretty decent shape, but the recent lack of exercise due to my kid (and laziness) quickly became apparent. We scrambled up some 3rd class ledges to gain access to the start of The Trough (or so we thought). We were already off route but we didn’t know it.

I could see that the route opened up above us. The Trough is a very distinct break down the west face of Tahquitz, and I felt confident we were in the right spot. We did a final gear check, and I felt good. I carried an enormous rack of gear, for fear of running out of pro. A double set of cams, 1.5 set of stoppers, plus some odd tri-cams and hexes. 12 shoulder length runners and a couple of 4-footers, plus a cordellete and my “emergency kit” which consists of an extra belay device, a small knife, two prusiks, and 2 lockers. Ryan would carry our approach shoes, a liter of water each, snacks and headlamps. He carried a bit of additional pro, just in case we needed it. I felt a little silly when, on the final pitch, a free soloist climbed past us with nothing more than a chalk bag attached to his harness.

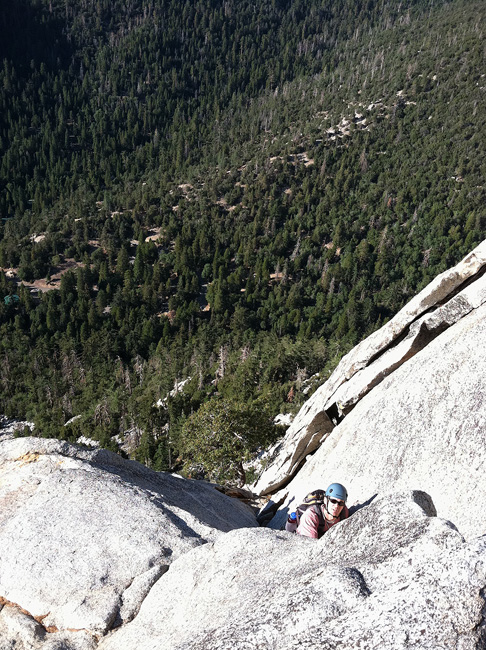

I should mention that these photos are all courtesy of Ryan, who brought along his Nikon DSLR. I had enough to worry about, and didn’t bring my camera. I did snap a picture of him topping out on the third pitch, using my iPhone. You can view his photo website here. Ryan is a relatively inexperienced climber, but he’s done some alpine mountaineering and he’s safety-conscious, and I am able to climb with confidence on his belay. He’s also fairly analytical (an engineer by trade) and we’re able to communicate well, all of which seems to lend itself well to trad climbing.

So, I set off on the first pitch, placing my first piece about 15 feet off the deck. Easy 5.5ish climbing across broken slabs, a bit runout in spots, and I reached a small tree at ~90 feet. Here, I was faced with a conundrum. I realized I was trending away from The Trough, and I found myself directly beneath an imposing roof. Yet, it still hadn’t occurred to me that I was off-route. I decided to build an anchor (picture below, upper left) and I brought Ryan up.

By now, an hour had passed and I could see some climbers in the chimney to our right. I called over and asked what route they were doing, and to my dismay they answered, “The Trough!!” Hmm… We were 50 feet to their left, and there appeared to be a few options. I could traverse across an exposed face, with dubious protection behind a thin flake, or I could try and climb up and over the roof, and then work my way across the ledge above. We discussed our options in democratic fashion and I decided to give the roof a try. A few reachy moves and I was able to surmount a big horn, but the climbing was starting to feel scary. I had no desire to climb anywhere near my limit, and I downclimbed back to the anchor.

Next, we considered a tension traverse, which looked simple enough. I would traverse over to the right using the tensioned rope as an assist, placing gear along the way. I felt confident as the leader, but never having done this before, I worried about the safety of the second (Ryan). In retrospect, I think it would have worked well, but neither of us felt confident enough to apply this theory to our very real situation. Instead of taking any risks, we decided to rappel off the pine you see pictured to my right, and we were safely back on the ground. Rather than view this as wasted time, I think it was a good learning experience (and a fun pitch of climbing).

Unfortunately, we found ourselves third in line behind two other parties, and we spent the next hour kicking around at the base. The clock was ticking, and I was getting antsy. We set off on the proper start at 12:18 pm.

The first pitch couldn’t have been more than 100 feet, up to a sturdy pine as a belay. There were some spicy, somewhat exposed friction moves near the top. The climbing wasn’t difficult, but it was more than I expected based on the rating. I gave a mental “thank you” to Tony Grice, who suggested we do The Trough instead of Angel’s Fright (5.7) as our first climb. Without a doubt, Angel’s Fright would have been more than I had bargained for. Ryan had coiled the rope using a mountaineer’s coil, and this seemed to introduce some twists which made feeding rope a real chore. As the leader, I found myself fighting rope drag and, at times, climbing faster than he was able to pay out slack. We decided to reflake the rope at the top of the next pitch, to clean out the twists. We also lost a 4′ sling, which became jammed on a chockstone I had slung for pro. Oh well, we needed to get moving and a sling isn’t a cam.

The second pitch, up the V-shaped, ledgy trough, was intimidating. I aimed for a large pine tree nearly 200 feet above us, which I knew was the next belay station. Opportunities to place pro were abundant, but the ledgy nature of the climb conspired against me. Halfway up, the rope drag was becoming fierce and I had burned through quite a bit of gear. I was out of sight from Ryan, and I found myself running it out on the easier sections, in order to preserve some gear for the uncharted territory ahead. The ledgy nature of the route seemed difficult to protect, in any case. I used my gear to protect against a major fall, accepting that a short tumble would likely result in a bashed knee or a broken ankle. I suppose this is reality of climbing such terrain.

The crux may have been the final few feet of the pitch. I worked my hands up a thin, polished crack with sketchy feet and arrived at a spacious ledge. Another climber was leaving the belay, and we talked for a bit. He recommended that I belay from pro set behind a flake, instead of the big tree, and I followed his advice. If I were to do it again, I would use the tree, which was 2 feet in diameter and unquestionably safe. I don’t mind a slightly less comfortable stance as a tradeoff for that security. My anchor appeared sound, though. In fact, Ryan was unable to clean my pink tri-cam. I was really starting to worry about the time, but rapping off at this point would have involved leaving gear, since we only had one rope. I brought Ryan up and I told him very frankly, “We have to hustle.” I wasn’t suggesting that we rush, but I wanted to be efficient and handle the belay transitions quicker. We had two pitches to go, plus the 4th class friction descent, which was still a wild card.

The transition went pretty quick, and I was off on the next pitch within a few minutes. The climbing was easier now, with big steps and ledges and I was running it out 10-15 feet, maybe more in places. I was moving up the rock with confidence, and I quickly reached the next belay (a tree). Looking ahead, I saw an even bigger tree another 40 feet up, and I decided to go for it. I knew it would be a rope stretcher, and Ryan confirmed (later) that I had indeed come close to the end of our 60 meter rope. Without a doubt, the longest pitch of climbing in my life. And it was fun, since I wasn’t nearly as scared as the previous pitches.

I anchored to the tree and used our non-verbal communication method that we had practiced at Mission Gorge. I quickly pulled up several arm lengths of rope as hard and fast as possible, to signal that it was safe to take me off belay. Twenty minutes later, Ryan’s head popped up above a little bulge and I let out a little shout of relief. All that remained was a short friction pitch to the top, and there was still plenty of light.

I scrambled up the friction slabs to the top, no more than 30 feet of easy, unprotected climbing. I placed myself amongst a pile of big boulders and then belayed Ryan directly from my harness. It must have been 5 pm, and I quickly gulped down a liter of Gatorade as we sat and admired our accomplishment. Ryan agreed that this Tahquitz 5.4 felt harder than some of the 5.9’s at Mission Gorge. The moves themselves might not have been terribly difficult, but the level of commitment and exposure brought a mental challenge that was far from trivial. The only time I’ve been so intimidated by something that was supposed to be fun is in heavy surf. It’s a mix of “Wow, this is awesome!” and “This is scary as hell, and I want it to be over now.”

The Friction Descent is a 4th class downclimb, and a popular method to descend from the top of Tahquitz. I had read reports ranging from “trivial” to “scary” and I wasn’t sure what to expect. We found the start without difficulty (thanks to online research) and getting off the rock wasn’t bad at all. There was mild exposure in places, but I never felt as if it were dangerous. We arrived at the base and followed a rough trail back around the west side and towards the start of our climb. We were still pretty high, and the path started splitting off in different directions with little forks here and there. This is where we made our final route-finding error, and we soon found ourselves lost in a thicket of manzanita, following the faintest of trails. What I originally thought were human footprints, I believe were actually animal tracks. An hour later, we were totally lost and darkness was rapidly approaching. Exhausted and hungry, I knew we had to move fast or risk having to navigate our way back to the trailhead in complete darkness. This wasn’t a life or death situation, but it was going to be a major inconvenience at the end of an already long day. We decided to head down the slope, following some faint game trails that would eventually lead to the bottom of the ravine. I used this technique when I got lost in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness during a snow storm, and it worked great. On that trip, I followed some mountain goat tracks which eventually led me back to the trail. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that animals know the best way to navigate their way around a mountain, and they use the same trails as we do (especially at night).

Twenty minutes later, we connected up with the Ernie Maxwell Trail, and I think we both felt a sense of relief. The sun was setting and we wouldn’t be spending the night bushwhacking our way back to the car. We ate dinner in Idyllwild and made it back to San Diego ~18 hours after the start of our day. A fine adventure, indeed.